Žurnal in English

WHAT LEGAL AMENDMENTS DO VICTIMS NEED: Suspended Sentences Do Not Affect Perpetrators

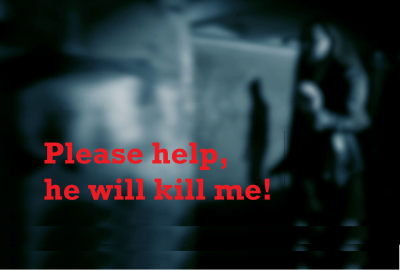

Is the ongoing presence of violence and cases of femicide the responsibility of the judiciary, society, a lack of prevention measures, or all of these combined?

In December last year, the Government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, at the proposal of the Federal Ministry of Justice, adopted the Draft Law on Amendments to the Criminal Code of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was submitted to parliamentary procedure. This law partially incorporates Directive (EU) 2024/1385 of the European Parliament and Council of 14 May 2024 on combating violence against women and domestic violence (OJ L2024/1385) into the legislation of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

During a previously organised discussion titled "A New Legislative Framework Against Gender-Based Violence in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Amendments to the Criminal Code and the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence and Violence Against Women", Justice Minister Vedran Škobić stated that the focus is on tightening penalties and introducing new criminal offences, such as stalking, female genital mutilation, misuse of sexually explicit content, and relations with children under the age of 15. However, the amendments to the Criminal Code do not include provisions criminalising femicide, as the Federal Ministry of Justice believes that the existing legal framework provides adequate protection for women in cases of femicide:

"The issue of femicide as a concept is essentially the murder of a woman out of hatred, which is already covered by our law," Minister Škobić explained.

These legislative amendments implement the Istanbul and Lanzarote Conventions, which Bosnia and Herzegovina ratified earlier. These conventions address the protection of women and children from all forms of violence, with a particular focus on domestic violence and the prohibition of sexual exploitation and abuse of children (Lanzarote Convention). The proposed law tightens penalties for perpetrators and prohibits the commutation of sentences for crimes against freedom and sexual morality, sexual abuse and exploitation of children, and crimes against marriage and family involving children. It also introduces new criminal offences, including sexual harassment, misuse of sexually explicit content, stalking, and other offences that could be exploited against children, as well as offences committed via information and communication technologies. The age at which a person is considered a child has been raised from 14 to 18 years, while a young adult is now defined as a person aged 18 to 21 years. The amendments also include provisions for the introduction of electronic bracelets for perpetrators, allowing authorities to monitor compliance with restraining orders and prevent the recurrence of criminal offences.

The Centre for Women's Rights has conducted judicial monitoring and analyses on gender-based violence for 12 years. Through their initiative, 70 per cent of the proposed material was adopted. While the Centre is pleased with these developments, they caution that after the parliamentary procedure and the law's enactment, its practical implementation must be closely monitored:

"We need to identify obstacles and shortcomings, determine which provisions need to be supplemented, and assess what is inadequate. Only then can we evaluate effectiveness. We work on judicial analysis related to gender-based violence and directly with women—over a thousand clients. This hands-on experience allows us to understand the impact of each legislative change. We will assess the situation once the law comes into effect. It’s too early to declare it either a success or a failure. Even the previous law could have been implemented effectively, but penalties were too lenient and below the minimum. Amending the law does not solve everything; we haven’t addressed the fundamental issues—such as fixing the institutions women first approach or raising awareness. Responsibility lies with all of us," says Meliha Sendić from the Centre for Women's Rights in an interview with Žurnal.

The law’s implementation, according to Sendić, depends on individuals within institutions:

"We lack a functioning system; all the links in the protection chain are not adequately connected. Multisectoral cooperation is minimal, and we often rely on the sensitivity of individuals within institutions—and fortunately, such individuals do exist. Responses to incidents of violence against women vary depending on the institution and the individual in charge."

Sendić highlights significant progress in the adopted legal framework, particularly the ability to sanction criminal acts committed via information technologies. Stalking, psychological violence, unauthorised publication, and sexual harassment committed through such means now carry penalties ranging from several months to five years. Previously, this form of harassment and stalking posed significant challenges for victims as it was not recognised in the criminal code. Threats made via social media or platforms like Viber can now be treated as criminal offences, enabling the filing of criminal charges:

"Until now, perpetrators of such acts often slipped under the radar," says Sendić.

The legislation was harmonised with the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence, but this represents a starting point rather than a conclusion to addressing violence against victims:

"We cannot say, ‘We have a law now, and the issue is resolved.’ The story is just beginning, and from the moment the law takes effect, we will monitor the work of institutions and their practices."

Although femicide has not been explicitly defined in the criminal code, Sendić explains that the term is already understood and the nature of such crimes is clear:

"Given how the system currently operates, neither I nor the experts applying this law believe that introducing the term into the legislation would improve matters. However, it might be beneficial in the future. What we advocate for now is stricter penal policies. The provision concerning aggravated criminal offences already allows for maximum penalties or increased sentences where applicable."

The murder of a woman by a spouse or intimate partner is gender-motivated, making it crucial for such acts to be explicitly recognised and sanctioned in criminal laws. Analyses of court rulings reveal that perpetrators often viewed women as their property, with victims killed because they were deemed to be "their women" who no longer wished to remain in the relationship—often after enduring years of abuse.

Zlatan Hrnčić, a senior advisor at the Gender Centre of the Government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and a doctor of sociology with experience in strategic prevention of domestic violence and human rights protection, elaborates on these findings for Žurnal.

He explains that this motivation is not evident in cases where men are victims of homicide:

"These murders could have been prevented with more appropriate sanctions and protective measures implemented at the time of the initial domestic violence reports. Evaluations of protective measures show no recurrence of violence when a combination of three actions is implemented upon the initial report: a 24-hour temporary detention to stop the violence, the imposition of a restraining order to provide space for action, and a six-month psychosocial treatment programme to teach the perpetrator new behaviour patterns. These three measures, when applied under the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence, combined with adequate sanctions under the Criminal Code, help prevent future violence and even the most severe cases that result in fatalities. In such instances, however, there is a need for a legal provision—whether femicide is defined as a specific criminal offence, classified within the existing murder statutes, or formulated differently—to make these gender-motivated killings visible," Hrnčić explains to Žurnal.

Regarding the necessity of amendments to the current laws (Criminal Code and the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence), one need only examine the most recent court ruling concerning violence perpetrated by Amir Džafić, a hotel owner in Jablanica, against his former employee, Enisa Klepo. In December 2023, during the first-instance proceedings, Džafić was sentenced to 10 months in prison after assaulting Enisa Klepo for requesting her earned wages. Following an appeal by the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton Prosecutor’s Office, the Cantonal Court in Mostar returned the case to the Municipal Court in Konjic for retrial. Džafić was again sentenced to 10 months, but under the still-applicable legislation, sentences of up to one year in prison can be converted into monetary fines.

From January 2023 to June of this year, public prosecutors in Bosnia and Herzegovina received 1,298 reports of domestic violence, but only 145 indictments were filed. The highest number of reports came from the Zenica-Doboj and Tuzla Cantons. According to unofficial statistical data, in around 70 per cent of convictions for domestic violence, a suspended sentence was imposed. Perpetrators are often repeat offenders of this crime. Therefore, an appropriate prison sentence at the earliest stages of abuse could help prevent the recurrence of the crime, ultimately preventing the most severe forms of violence that result in murder.

Sarajevo-based lawyer Dr Amila Mujčinović explains to Žurnal that a suspended sentence or prison sentence rarely has a rehabilitative effect on the perpetrator, especially if they return to live with the victim:

Certainly, a prison sentence plays a greater role in reformation than a suspended sentence - as a milder penalty.

JUDICIAL PRACTICE

In the document Judicial Response to Femicide in the Western Balkans (The AIRE Centre), the research focused on the practice of courts in prosecuting femicide and attempted femicide. Since femicide is not criminalised as a separate offence in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the research sample included cases concluded between 1 January 2017 and 30 June 2021, relating to prosecuted criminal acts in which the perpetrators were men and the victims were women. A total of 34 cases were analysed (26 decided by courts in the Federation of BiH, seven by courts in Republika Srpska, and one by courts in Brčko District of BiH).

The largest number of all criminal offences was committed in the victim's apartment/house/yard (35.3%), which confirms the results of previous research on violence against women, showing that a woman's home is the least safe place for her. An interesting fact is that as much as 20.6% of criminal offences were committed at the victim's workplace, indicating the great audacity and recklessness of the perpetrator, as well as the increased social danger posed by these criminal acts. A large number of offences were committed in the shared apartment/house/yard of the perpetrator and the victim (17.6%), which could have been expected due to the nature of the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator (marital, common-law, emotional relationship, kinship) and their life together in the household. The perpetrators used firearms (hand grenade, pistol, automatic rifle – 35.3%) more frequently when committing criminal offences than cold weapons (knife/cutlass, scalpel, hammer, metal rod, blunt object – 29.3%) and physical force (8.8%), which can be explained by the illegal possession of firearms, mostly originating from the war period. The largest percentage of criminal offences, 23.5%, were committed using multiple means of execution to more easily overcome the victim's resistance, which manifests the special brutality and cruelty of the perpetrator towards the victim – as stated in the analysis.

The study sample included 35 perpetrators. Most of them were aged between 33-40 and 49-59 (20% each). The youngest perpetrator was 18 years old, and the oldest was 72 years old. In terms of prior convictions, the majority (60%) had not been previously convicted, while 40% had committed a prior crime. From the analysed court decisions, it can be concluded that the courts generally referred to mitigating and aggravating circumstances, as stated in the law, without a detailed analysis of their significance. For example, courts considered the following mitigating circumstances: admission of guilt; expressed remorse; family circumstances (married, family man, number of children: father of two or more, eight children; family conditions related to the primary family, growing up without a mother, parental love, care; financial conditions, unemployment; age of the perpetrator, health condition (poor health, psychological issues, treatment in a psychiatric clinic, disability, surgery); reduced accountability, but not significantly; good conduct during the trial; prior good conduct; actions as a result of impulsive emotions caused by alcohol rather than planning; psychological immaturity, insufficient awareness of the act and consequences; psychological consequences of war trauma; the victim does not support the criminal prosecution.

The recognition of mitigating circumstances in practice was discussed in a previous article, where a repeatedly convicted perpetrator was once again given mitigating circumstances such as remorse and a "critical life period" through which he was going.

In the period from 2019 to 2021, N.N. (identity known to the editorial team) and her surroundings were victims of violence and terrorisation by A.H. from Sarajevo. The victim first reported the violence to the competent authorities in 2020.

"I went through bureaucratic torture and the organised protection that the police of the Sarajevo Canton (MUP KS), the Cantonal Prosecutor’s Office of Sarajevo Canton, specifically Sabina Sarajlija, Meliha Dugalija, assistant Edin Pirija, and others, in collaboration with prominent lawyer Edina Rešidović, and other lawyers from the Rešidović Sabrihafizović law firm, who represent the mentioned perpetrator in all cases before the court and who also represented his father, a general of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, before the Hague Tribunal. Some of the people close to this case were also represented by lawyer Nermin Mulalić, who also represented Sabina Sarajlija in her disciplinary procedure due to irregularities in her work as the main cantonal prosecutor," N.N. told Žurnal.

A.H. confessed to his guilt, and in September 2021, the Municipal Court in Sarajevo sentenced him for causing light bodily injuries, imposing a one-year conditional sentence. In deciding the sentence, the Court considered the confession at an early stage of the proceedings, "expressed remorse", and the fact that he had no prior convictions as mitigating circumstances. There were no aggravating circumstances.

In the new sentence for another act of violence, the same outcome – a conditional sentence. The decision to impose a conditional sentence, in this case, is again based on the fact that the defendant admitted committing the crime, and although he had been previously convicted for a similar offence, the court found that after the first conditional sentence in 2021, "he had no further conflicts with the law", was in a "critical life period", had accepted "responsibility for his actions", and would henceforth respect the legal system and refrain from committing similar criminal acts:

"...at this moment, the execution of a prison sentence is not justified, but it is justified to give the defendant a chance to prove that this behaviour is truly a thing of the past in his life and a result of a critical life period," the ruling stated.

Is the responsibility for ongoing violence and cases of femicide with the judiciary, society, or a lack of prevention? Or is it a combination of all? Zlatan Hrnčić told Žurnal that in cases of reported domestic violence, the involvement of a large number of professionals in this multisectoral chain of action is crucial:

"If we break it down into numbers, we see that annually in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there are 7,000 police interventions, considering that at least two police officers respond to each report (annually, there are around 3,500 reports of domestic violence). Then, prosecutors, judges, healthcare workers, and social workers who monitor all protective measures, which were around 3,000 last year, are involved. In the 10% of the most severe cases of violence, placement in safe houses is also realised. In this chain of action, if even one link is missing, it leaves room for an incomplete response. Given this, it is essential to implement comprehensive multisectoral education, as well as specialised professional training, so that all actors in this chain of action have the necessary sensitivity and understanding of the procedures of all professionals involved. In fact, it is not enough for everyone to do their part of the job; it is necessary that everyone does their part of the job properly."

Strategic and comprehensive action is guaranteed by the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence, which defines a mechanism related to the Strategy for the Prevention and Fight Against Violence at the federal level of government, as well as strategic documents at the cantonal and local levels, he cautions. This strategic approach is also directly linked to the implementation of internationally defined standards and obligations, particularly those of the Istanbul Convention. Full implementation and support of these officially adopted documents within the defined timelines can lead to a society with zero tolerance for domestic violence and timely, adequate responses from institutions:

"Considering that decision-makers are making decisions in various areas of social life, sometimes I believe that the implementation of obligations under these documents is not taken seriously enough. When certain omissions occur, they are often linked to temporary solutions instead of focusing on more serious support towards establishing sustainable systemic solutions."

In November 2023, we reported that a revision identified numerous shortcomings in the victim protection system. Legislation in the field of social policy does not recognise victims of violence as a category of social protection beneficiaries in all cantons. The report Gender Equality and Prevention of Violence Against Women, published in October by the Audit Office for Institutions in the Federation of BiH, warns that between 2019 and 2022, only one perpetrator was subjected to the measure of temporary deprivation of liberty, even though, for example, in 2022, 278 individuals were subject to measures prohibiting proximity to the victim.

None of the safe houses in the Federation of BiH were established by competent institutions, but by non-governmental organisations: Žene sa Une in Bihać, Vive žene in Tuzla, Medica in Zenica, Žena BiH in Mostar, and the Local Democracy Foundation in Sarajevo.

"Although this is a legal obligation, the minimum standards that safe houses must meet, including those regarding premises, equipment, and staff, have not yet been established in the Federation of BiH. The standard recommended by the Council of Europe is one place in a safe house per 10,000 inhabitants. The available capacity in the Federation of BiH is 126, which is 57% less than the required number according to the Council of Europe standard," the report states.

The law stipulates that safe houses are funded 70% from the federal budget and 30% from the cantonal budget. Between 2019 and 2022, safe houses were allocated a total of 3.1 million KM, with 37% from the federal budget and the remainder from cantonal budgets. Audit data show that the allocated funds do not cover the total costs of the professionals working in the safe houses and other expenses.

The establishment of safe houses has proven to be an excellent model that functions effectively within this system, and the Centres for Social Work play an irreplaceable role by directing victims to safe houses. The police, who are trained and aware of how to direct victims to safe houses and contact the Safe House Centre, also play a key role, says lawyer Dr. Sci. Amila Mujčinović for Žurnal:

"In this context, I want to emphasise that even after a prison sentence for the perpetrator, we had a situation in the Maslan case where the violent individual, after serving their prison sentence, killed the victim. I believe the main problem lies in monitoring the perpetrator, particularly during the critical period after a conviction, and to ensure this, the legal norm must be changed. On the other hand, a weak link in the whole system is the lack of adequate psychosocial support for victims, which hinders their recovery or change of environment. As a result, victims often change their stance and opinion, making it more difficult for the judiciary to complete the process."

According to the proposed law, which now also addresses safe houses, they will be partially institutionalised, receiving funding from the budget, and communities in need can request the establishment of new safe houses.

The case of the murder of Alma Kadić from Sarajevo serves as a stark example of judicial practices, procedural shortcomings, and administrative pitfalls. The Supreme Court of the Federation of BiH sentenced Eldin Hodžić to a unified prison sentence of 20 years for the murder of his wife, Alma Kadić, in July 2021, as well as for unlawful possession of a weapon and violating a probation sentence for a previous conviction. This is 15 years less than the 35-year sentence handed down by the Cantonal Court in Sarajevo, to which the defendant appealed. The Supreme Court explained that the first-instance sentence issued by the Cantonal Court was "non-existent" and not foreseen by the Criminal Code of the Federation of BiH. The Court also considered mitigating circumstances for each criminal act for which a sentence was issued, such as domestic violence and unlawful possession of a weapon.

The Supreme Court clarified that this decision resulted from the Cantonal Court's failure to correct an error made in the first-instance sentence. The initial sentence was annulled, with the explanation that there is no 35-year prison sentence but only a long-term sentence of 35 years, which the Cantonal Court had failed to correct upon re-issuing the first-instance decision. A complaint regarding the actions of the judicial institutions in this case was officially registered by the Office of the Disciplinary Prosecutor (VSTV).

In the statement released by the Fondacija Cure after the verdict, it was noted that the drastic reduction in the killer’s sentence "symbolises the failure of the judicial system":

"The decision of the Supreme Court of FBiH to reduce the sentence from 35 to 20 years sends a message that procedural errors carry more weight than a woman's life. This case clearly shows how deficiencies in the judicial system not only fail to protect women but also allow perpetrators to receive lighter sentences. Protests were necessary to highlight the need for judicial reforms, as well as to show solidarity with all women currently in violent relationships."

The system reveals obvious deficiencies at all stages – from reporting violence, through effective victim protection, to appropriate punishment of offenders. Procedural errors, like those in the Alma Kadić case, become tools for reducing sentences, instead of ensuring the judicial system delivers fair rulings. Despite protection measures and reports of repeated threats and attacks, institutions failed to take concrete steps to prevent the escalation of violence. Judicial and police officers often do not understand the seriousness of domestic and gender-based violence, further discouraging women who are enduring violence from reporting it.

"Preventing femicide requires cooperation between the judiciary, police, and social services, but this coordination is nearly non-existent. Victims' trust in the system is extremely low. Women who report violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina generally do not trust the system, which is the result of long-standing failures at all levels – from police and social services to the healthcare sector and judicial institutions. Women who report violence often face dismissive approaches from institutions, their complaints are ignored, and the slow processes further traumatise them. When rulings, like those in the Alma Kadić case, favour procedural errors over justice, it sends a message that even the most severe crimes do not guarantee strict and fair sentences. Victims are discouraged, and perpetrators are encouraged," said Fondacija Cure, warning that trust can only be rebuilt once the judicial system effectively punishes perpetrators, the police and judiciary consistently apply laws, and protection for victims is ensured through a comprehensive and coordinated approach.

(zurnal.info)