Žurnal in English

PEDOPHILIA IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA: A Corrupt System Punishes Victims and Protects Child Abusers

In Republika Srpska, 250 individuals have been registered as paedophiles since the registry was established in 2018. In the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, there has yet to be a comprehensive listing of all individuals with final convictions for paedophilia. Incidents of paedophilia are on the rise throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. From January 1 to December 31, 2023, the Banja Luka District Public Prosecutor's Office received 47 reports of sexual assault on minors and filed 31 indictments.

The public revelation that the well-known Bosnian actor Muamer Kasumović was convicted of indecency involving a minor and secretly bought off a one-year prison sentence—set by the Sarajevo Municipal Court in 2023 for 36,500 BAM—has provoked widespread outrage and condemnation. Kasumović has been ostracised from the professional community in Bosnia and Herzegovina and has since left the country.

Beyond the shocking fact that he paid off a prison sentence for the heinous act of sexually abusing a minor, the manner in which his crimes came to light is also disturbing. If the young man—who, according to his testimony, was Kasumović's victim of sexual abuse—had not mustered the courage to recount his trauma to the audience after a performance at Sarajevo Fest, the actor would have likely continued his life unimpeded, waiting for a potential new victim.

This is further supported by the young man’s testimony that he was not Kasumović's only victim and that there was another legal process involving the actor. The public, however, has yet to receive answers to crucial questions: Who influenced the court to keep Kasumović’s conviction under wraps? And how could it be that for three years, no one knew he was reported for indecency involving a minor, that an indictment was filed, and that a conviction had been rendered?

WHY WAS THE CONVICTION HIDDEN?

There is no doubt that those in the court who concealed the conviction, along with those who influenced its suppression, are Kasumović’s accomplices. From the moment he was reported for sexually abusing a minor until his public exposure, they knowingly put every child who came into contact with him at serious risk.

“It’s a double-edged sword because the interests of minors are protected, and cases involving them are often not made public, which they use as justification. But that’s not the deception. The deception lies in how the court publishes its decisions. You have ten offenders convicted of similar crimes (sexual abuse of a child, violence against a child, etc.), and their verdicts are made public, with all the consequences that come with such exposure. Kasumović’s name, however, is absent. For some people, the court omits to show that a case was filed. This loophole was precisely what was exploited in Kasumović’s case,” Sarajevo-based lawyer Vlado Adamović told Žurnal.

Adamović argues that a lobby exists to protect child abusers, including paedophiles. He supports this claim by pointing out that, for certain individuals, court records are not made public, mandated actions under the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence are bypassed, and members of these lobby groups include people from law enforcement and judicial institutions, as well as psychologists and forensic experts who, as he puts it, have “set up shop” within prosecutors' offices. Together, they form a corrupt network that works against the interests of children, despite international conventions from the United Nations and the Council of Europe resolutions emphasising that children’s interests should be paramount.

Adamović continues, stating that numerous cases exist where responsible institutions—from social work centres to police, prosecutors, courts, psychologists, and forensic experts—fail to adhere to required anti-corruption standards and bypass provisions of the Law on Protection from Domestic Violence.

“Psychologists can exploit the premise that every child has the right to see both parents, regardless of what has happened. This is extensively abused in our country; they say, ‘Let the criminal proceedings determine if he raped the child, but he should still see the child.’ The Law on Protection from Domestic Violence explicitly prohibits this. By sidestepping this law, you’re effectively giving paedophiles an advantage. This is done in favour of doctors, prominent businessmen, and tycoons, whereas those from poorer backgrounds end up in custody within 24 hours,” Adamović explains.

Banja Luka-based attorney Milan Malešević shares similar concerns, saying the question of a potential lobby within judicial institutions that shield paedophiles is serious and requires thorough investigation.

“While it's difficult to definitively confirm the existence of such a lobby without concrete evidence, the fact that some individuals manage to evade serving their sentences suggests issues with legal enforcement and procedural transparency. It’s essential for the relevant institutions to investigate these claims and uphold the integrity of the judicial system. Any form of concealment or support for convicted paedophiles is unacceptable,” emphasises Malešević.

The Kasumović case led to the creation of a paedophile registry in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had been anticipated for five years. This registry records individuals with final convictions for crimes against the sexual freedom and morality of children and minors in FBiH. The registry is permanent, with data that cannot be erased. Although it will not be public, all public and private institutions directly or indirectly working with children will have access to it. They can verify potential employees by submitting names to relevant Ministries of Internal Affairs for screening. Republika Srpska established a similar registry earlier, in 2018. Individuals on that list are required to report all travel, and any change in personal information, and are prohibited from visiting locations where children gather. The entities, including the Brčko District, are obligated to share data on individuals listed in the paedophile registries.

Attorney Malešević notes a difference between RS and FBiH in their criminal policies on child sexual abuse, with RS adopting a stricter approach.

“In RS, under Article 172 of the Criminal Code of Republika Srpska, the basic offence of sexual intercourse with a child under 15 is punishable by 2 to 10 years in prison. If the offense is committed by a close relative or involves force, the minimum sentence rises to 8 years. In cases with severe consequences, such as the death of the child, sentences range from a minimum of 10 years to life imprisonment. By contrast, Article 207 of the Criminal Code of the Federation of BiH sets a penalty of one to eight years for basic offences involving sexual intercourse with a child. For cases involving force or abuse of authority, sentences range from three to 10 years, and for severe consequences, penalties range from five years to long-term imprisonment. This difference in criminal policy highlights a stricter approach in Republika Srpska toward the basic offence, although both entities recognise the gravity of child sexual abuse,” he explains.

However, Malešević emphasises that the most significant difference between the criminal legislation of the two entities is that in RS, it is not possible to pay off a prison sentence (imposed up to one year) for this type of crime, while in FBiH, this option is allowed.

“This was exploited by actor Muamer Kasumović, leaving the public in shock and raising the question: How was it possible that no one knew about his conviction?”

Two cases from Republika Srpska illustrate some of the ways paedophiles manage to avoid prison sentences.

CASE ONE

On November 7, 2023, Ivica Mišković from Kakanj escaped through a window of the Basic Court in Banja Luka after being handed a first-instance four-year prison sentence for the aggravated sexual abuse of a young girl. Mišković seemed to have vanished without a trace, only to resurface about ten days later on Zagreb’s Nova TV, where he confirmed his escape to Croatia, a country where he holds citizenship.

“I believe in God, and He helped me escape from the detention unit. I crossed the Croatian border illegally, on a bicycle,” Mišković told the station’s journalist, claiming he was “wrongly convicted.”

There was no “divine intervention” involved in Mišković’s escape from the detention unit, nor was it a coincidence. It is clear that he had support arranged in advance. After the sentence was handed down, he was brought to the detention unit without handcuffs, which, as initially reported, allowed him to push a court police officer and jump through the courthouse window, disappearing into a crowd in broad daylight in Banja Luka. Everything points to Mišković having at least one accomplice, if not more, who were waiting for him near the courthouse to help transport him to the Croatian border as previously arranged. The two court police officers who escorted Mišković to the detention unit were immediately suspended, and later a disciplinary process was conducted, resulting in their dismissal.

“The employment of these officers was terminated as of April 25, 2024, so they are no longer members of the RS Court Police,” confirmed RS Court Police Director Željko Dragojević to Žurnal.

Dragojević added that the responsible institutions had not notified the RS Court Police of any investigation launched to determine the criminal liability of these former officers. Banja Luka’s District Prosecutor’s Office confirmed to Žurnal that on March 8 of this year, the RS Ministry of Internal Affairs submitted a report to this office against two individuals, T.D. and T.D., for the criminal offence of “Facilitating the Escape of a Person Deprived of Liberty,” under Article 345, Paragraph 1 of the RS Criminal Code and that the case is currently under review by the assigned prosecutor.

The investigation should determine whether, and by whom, the two court police officers were hired to assist Mišković in escaping from the courthouse, or if, as some media have previously reported, Mišković exploited the inexperience of one of them and fled through a window.

On November 8, 2023, the day after his escape, the Basic Court in Banja Luka issued an order to issue a warrant.

"Through a review of the CMS system (Automated Case Management System), we determined that the international warrant under which the named individual was originally arrested remained in effect, even though he was in custody. Consequently, on November 8, 2023, the court issued an order for a warrant after receiving a letter from the Banja Luka District Center of the Court Police. Given that an international warrant was in effect, this provided police agencies with grounds to detain the individual," the Basic Court in Banja Luka responded to Žurnal.

A specific challenge in bringing paedophile Ivica Mišković to justice is that he found refuge in Croatia, where he holds citizenship in addition to his Bosnian citizenship.

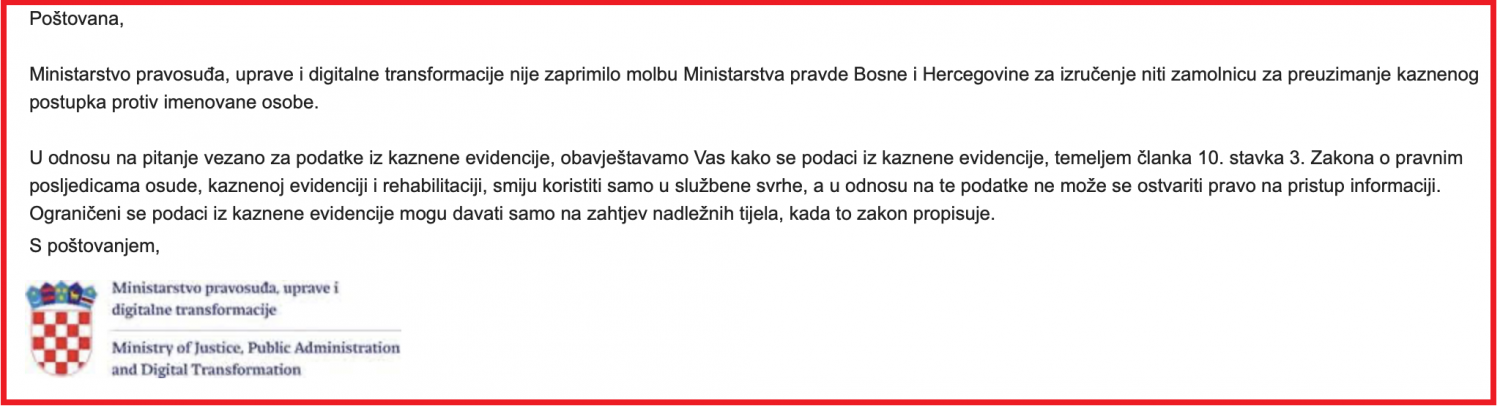

In their response to Žurnal, the Basic Court in Banja Luka stated that on January 5 of this year, they received a document from the Ministry of Justice and Administration of the Republic of Croatia, dated December 27, 2023. The document listed the reasons why the request for Mišković's extradition to Bosnia and Herzegovina was not granted, explaining that the legal conditions required by the 2012 Extradition Treaty between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were not met. Specifically, the crimes committed by Mišković are not covered by the Extradition Treaty, and the prison sentence imposed by the non-final judgment does not meet the criteria in Article 8 of the Treaty. The Basic Court also noted that Mišković's case is now with the Banja Luka District Court for appeal consideration.

Considering these statements from the Basic Court in Banja Luka, it is surprising that the Ministry of Justice and Administration of Croatia told Žurnal that it “has not received an extradition request from the Ministry of Justice of Bosnia and Herzegovina or a request to take over the criminal proceedings against the named person,” meaning Ivica Mišković. Equally surprising is the response from Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Ministry of Justice, which states that Ivica Mišković was extradited from the Federal Republic of Germany to Bosnia and Herzegovina on June 22, 2022 and that the Ministry “does not have any additional information regarding the individual in question.”

According to a document in the possession of Žurnal, it is clearly stated that the Ministry of Justice of Bosnia and Herzegovina sent a request for Mišković's extradition to the Ministry of Justice of Croatia on December 20, 2023 and that a negative response from the Croatian ministry arrived seven days later, as indicated by the Basic Court in Banjaluka in its response to Žurnal.

Given that there is still an international warrant for Mišković, we asked the Croatian Ministry of the Interior whether they are searching for him and if his name is registered in the paedophile registry in Croatia. The Croatian Ministry of Internal Affairs directed us to seek all answers from the Ministry of Justice of Croatia, which responded that, according to the law, data from criminal records may only be used for official purposes and that access to these records cannot be granted.

Many media outlets have previously stated that Mišković deceived the system, but it is also true that the system failed Mišković's victim, the girl he sexually abused, and her family. And not just them. Due to bureaucratic obstacles to Mišković's extradition to Bosnia and Herzegovina, he is freely walking around Croatia, and possibly even in another EU country now.

CASE TWO

Milenko Tomić, the former president of the Boxing Federation of RS and the general secretary of the Boxing Federation of BiH, failed to appear in the District Court in Bijeljina on March 29 of this year for the pronouncement of a sentence in which he was convicted to 12 years in prison for the charge of having sexual intercourse with a fourteen-year-old girl. The last time he was at his home address was two days before the sentencing. Since then, he has completely vanished.

Before his escape, he was under house arrest, and the police were visiting him twice a day until the evening of March 27, when they could not find him at his residence. The proceedings against him lasted more than two years, and the District Prosecutor's Office in Bijeljina publicly warned that the court was prolonging the process to exhaust all legal options to extend Tomić's detention. He was placed under house arrest from which he escaped two days before the verdict was pronounced. The District Court in Bijeljina claims it is not true that the court deliberately delayed the proceedings.

"This court extended the defendant's detention to the maximum legally prescribed duration, despite the fact that the Constitutional Court of BiH in its Decision on the admissibility and merit number AP -1017/23 of March 21, 2024, determined that further extension of detention, which was extended by the Supreme Court of Republika Srpska, was unfounded," the Bijeljina District Court responded to Žurnal.

They noted that the court "exhausted all legal possibilities to keep the defendant in detention, and the claim that this court, or the panel, deliberately enabled the defendant's escape is arbitrary." They pointed out that when observing the entire case, one must consider how long the prosecution presented evidence during the trial, how long the defence presented evidence, and how many times the defendant changed lawyers, a right the court could not contest.

Since there was no legal possibility for Tomić to remain in custody, they stated, the judicial panel decided to place him under "house arrest," with all prohibitory measures and an obligation for the police to monitor compliance with those measures.

"Therefore, the court utilised all legally permitted measures to ensure the defendant was available to the court, and the legal obligation to enforce these measures rests, according to the law, with the police authorities," emphasised the court.

In response to earlier claims from the Bijeljina District Public Prosecutor's Office about warning the court that the deadline for Tomić's detention was approaching, they stated that "there is no act that was submitted to the council or the court indicating that there was knowledge or evidence that the accused would flee."

"If the prosecution had this information, it was obligated to act and provide the police with these facts, and even this council, so that measures could be intensified. To our knowledge, there is no such act," the Bijeljina District Court stated.

They emphasised that the prosecution is not a supervisor that assesses the legality and correctness of court procedures and decisions and that the Supreme Court of RS will give the final word on the legality of the Bijeljina District Court's actions in this case. Meanwhile, the chief prosecutor of the Bijeljina District Public Prosecutor's Office, Olga Pantić, has been temporarily removed from this position. The decision to suspend her was made by the First Instance Disciplinary Commission of the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina, following a disciplinary complaint filed against Pantić based on multiple grievances and reports against her. Among other things, as reported by some media, it was due to the prosecution's involvement in the "Tomić case."

Tatjana Savić, the attorney representing the victim and her family, previously stated for Banja Luka's "Nezavisne novine" that she expects the police to do their job regarding the warrants issued for Tomić. The verdict against Tomić was posted on the court's notice board and was also delivered to his lawyer, Veselin Londrović, who claims he has no idea where his client is.

THE LAW FAVORS PEDOPHILES

In this case, the system has once again failed the victim. Predator Tomić moves freely, potentially lurking for new victims instead of serving his sentence. It is possible that he holds dual citizenship in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. Banja Luka lawyer Milan Malešević believes that the practice of evading punishment by fleeing to neighbouring countries is a particularly significant issue.

"This situation highlights a serious legal vacuum and a lack of coordination among states in the region regarding the extradition of convicted individuals. Specific cases, such as Ivica Mišković and Milenko Tomić, who have exploited dual citizenship to escape judicial systems, demonstrate an inappropriate abuse of legal loopholes. Addressing these situations requires stronger cooperation between the judicial institutions of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, as well as more effective international warrants and extradition agreements," emphasises Malešević.

In Republika Srpska, 250 individuals have been registered in the paedophile registry established in 2018. In the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, all those who have been definitively convicted of paedophilia still need to be recorded. Paedophilia is on the rise throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. From January 1 to December 31, 2023, the District Public Prosecutor's Office in Banja Luka received 47 reports of sexual abuse of minors and filed 31 indictments. During the same period, 15 indictments were filed for the crime of "Exploitation of Children for Pornography."

The Bijeljina District Prosecutor's Office has issued three orders for investigations into sexual abuse and exploitation of children since the beginning of this year. The most severe case of paedophilia in Bosnia and Herzegovina's history was recorded in Laktaši. Dragan B. was sentenced in 2022 to a cumulative prison term of 15 years for the sexual abuse of three girls under the age of 15.

In some countries, such as Belgium, Norway, North Macedonia, Poland, and the USA, the paedophile registry is public. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as its entities, it is not. Therefore, all responsibility lies with the system—to make it clear to predators who prey on children, both in real life and online, that there exists a system that maximally protects and cares for the rights of minors.

This can best be achieved through a strict penal policy and the imposition of appropriate prison sentences, which will not only put paedophiles behind bars, where they belong but also encourage society, especially victims, to report such cases.

"That's the damn money. There are red lines below which, regardless of legislation, society cannot go. It is completely unacceptable for someone to bribe an expert to save a husband who raped a six-year-old child," concludes Adamović.

(zurnal.info)